Idea

Third places, true citizen spaces

By Ray Oldenburg and Karen Christensen

Sun streaming through tall windows, steam rising from fat china mugs, the fragrance of roasted beans and fresh yeasty rolls, and the steady background sound of conversations, laughter, and cups clinking. This is where friends meet, where neighbours share news, where business is done, where strangers start talking. This is a third place.

It was the sociologist Ray Oldenburg – co-author of this essay – who coined the term “third place” in his 1989 book The Great Good Place, a surprise bestseller and a New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice. The third place is not home and not work, but instead one of the physical settings that have throughout history encouraged a sense of warmth, conviviality, and that special kind of human sustenance we call community. These settings include cafés, taverns, libraries and hair salons, where people from different walks of life gather to hang out in an informal atmosphere.

The term “third place” quickly entered the common lexicon. Ray Oldenburg’s admirers around the world have looked to his book to find ways to promote social cohesion by designing physical spaces that promote a sense of community. Readers said that the book had given a name to something they knew and cared about but hadn’t had a way to talk about.

This simple concept reminds us that human connections need nurturing and that community depends on such simple things as a few tables, a friendly host and a willingness to see what happens when we get together face-to-face.

The notion of a "third place" reminds us that human connections need nurturing

When the COVID-19 lockdowns started, a Boston reporter asked if we thought third places would ever come back. We answered with a resounding “Yes!”: we knew that Zoom meetings and happy hours would never replace face-to-face interaction.

Nothing contributes to a sense of belonging in a community as much as membership in a third place. But a lot of places that are advertised as third places don’t measure up. Despite being valuable public places - such as street markets and pedestrian shopping streets – they are not the kind of places Oldenburg had in mind.

The third place, typically, is a watering hole of one sort or another, and conversation is the main activity. The general rule is that beverages are of such importance as to become veritable social sacraments. Indeed, the majority of the world’s third places have drawn their identity from the beverages they have served. There are or have been ale houses, tea houses, soda fountains, wine bars and milk bars, Biergärten in Germany, gin palaces in England, 3.2 joints in the United States, etc. The Czech kavama, the German kaffeeklatsch, the French café – all derive from the respective words for coffee.

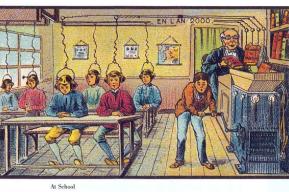

Embryo of democracy

Coffee houses began in the Middle East, and their heyday as a third place was in England during the 17th century. Coffee was considered dangerous when it was first introduced in Europe as coffee houses became the preferred location for political debate. In 1650, an entrepreneur remembered only as Jacob opened the first coffeehouse in Oxford. Shortly thereafter, others were opened in Cambridge and London. The coffeehouse and its “bitter, black beverage” were initially regarded as a novelty – but not for long. The democratic atmosphere of the coffee house, its equally democratic prices, and the pleasant contrast it offered to the drunkenness that plagued the inns and taverns of the 17th century brought it quick popularity.

When King Charles II tried to suppress the coffee houses in 1675, there was such a mighty public outcry that he retracted the edict ten days after. As places of free speech allowing a certain level of equality, coffee houses can be seen as the precursors of democracy.

Coffee spurs the intellect; alcohol the emotions and the soma. Those drinking coffee are content to listen contemplatively to music, while those drinking alcohol are inclined to make music of their own. Dancing is commonly associated with the consumption of alcoholic beverages but not at all with coffee sipping. Reading material is widely digested in the world’s coffeehouses but not in bars. The dart player drinks ale, but the chess player’s drink is coffee.

Penny University

In England, the coffee house was often referred to as the Penny University. A penny was the price of admission to its store of literary and intellectual flavours. Two pence was the price of a cup of coffee; a pipe cost a penny; a newspaper was free. The coffee house of the seventeenth century was the precursor of the daily newspaper and home delivery of mail, and the centre of business and cultural life as well as a political arena.

The coffee house of the seventeenth century was a real political arena and a place to read newspapers

Many of the nation’s largest trading companies were headquartered in the coffee houses, and London’s stockbrokers operated within them for over a hundred years. Only when those establishments fell into decline did the brokers finally acquire their own quarters and establish an Exchange. For many years, the insurance institution Lloyd’s of London operated out of a coffee house, which provided a place where the city’s unorganized marine underwriters could mingle with knowledgeable men of the sea and benefit from their gossip. The coffee house was fundamentally a forum for human association and community, both practical and deeply satisfying.

New perspectives

The need for such a society can hardly be said to have disappeared. While vibrant third places have become rare, it is possible to identify factors that help them survive and thrive. Atmosphere matters, and so does location and outlook. French culture, for example, has preserved a man-made environment that is both aesthetically pleasant and built to human scale. Throughout modern times, the desire to retain the life of the street has prevailed. Even in Paris, where cars are everywhere, the life of the street and that of the bistro persist side by side.

Another example is the Viennese coffee house, a model of the third place. Save for the dark period under the Nazis (who favoured beer halls but feared coffee houses), the cafés of Vienna have never really waned in vitality or popularity. This description from a 1931 guidebook The Vienna that's not in the Baedeker by T. W. MacCallum could be a model for the kind of coffee shop we need today:

“The place for them all, a meeting place for lovers, a club for people of common tastes or interests, an office for the occasional businessman, a resting place for the dreamer, and a home for many a lonely soul.”

The meteoric growth of chain-owned and branded coffee houses that began in the early 1990s was in part based on the idea of a friendly, life-infusing third-place experience. Mobile technology as well as the pandemic have, however, dramatically changed the business model. Some 80 per cent of chain coffee house businesses are now offering drive-through and mobile orders. Claims that they can make a mobile app into a virtual third place have been met with considerable scepticism. This opens new possibilities for locally owned coffee shops, as well as other businesses with third-place potential.

It's time to reinvigorate the third place for discussion, debate, camaraderie and laughter. We need to see our friends and neighbours and to be around people we don’t know. The third place is at the centre of our search for a better way to live.

Ray Oldenburg

Professor emeritus in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of West Florida in Pensacola, USA, and author of The Great Good Place. Co-author of this article, Ray Oldenburg passed away on 21 November 2022, a few months before its publication in The UNESCO Courier.

Karen Christensen

Editor and essayist and co-author of a forthcoming, expanded edition of The Great Good Place.

What makes a place a third place?

- It’s neutral ground. You don’t need an invitation, and anyone can enter.

- It’s unstructured. You can come and go as you please.

- It’s not expensive.

- It’s a place to talk. Conversation is the main activity, though playing games like chess and mahjong is also common.

- It’s near your home or work place. Ideally, you can walk to your third place.

- It has regulars. But strangers aren’t out of place.

Chatter, joking and teasing are an integral part of a third place.

In the same issue